ᑲᔪHᐃᐅᑎHᐃᒪᔭᑦᑲ - Kajuhiutihimajatka: A Conversation with Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona | Jesse Ruddock

May 18, 2022

Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona, Tiriganiaq, 2022, felt and embroidered thread, 117 x 96 cm | image: Nathan Saliwonchyk

Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona’s current exhibition at the Art Gallery of Guelph presents her work alongside that of her grandmother Victoria Mamnguqsualuk (1930–2016) and great-grandmother Jessie Oonark (1906–85). ᑲᔪHᐃᐅᑎHᐃᒪᔭᑦᑲ - Kajuhiutihimajatka - What I’m Carrying On presents a thriving artistic lineage from Qamani’tuaq, Nunavut’s sole inland community at the mouth of the Thelon River on the shore of Baker Lake. The exhibition grew from a collaboration with co-curators Taqralik Partridge and Shauna McCabe, with the artist leading a foray through the gallery’s extensive Inuit art collection. During a months-long residency at the gallery, Uyagaqi Kabloona, typically a ceramicist and printmaker, created her first wall hanging that is now a feature of the exhibition: Tiriganiaq is a retelling—with a twist—of the legend of Kiviuq’s Fox Wife.

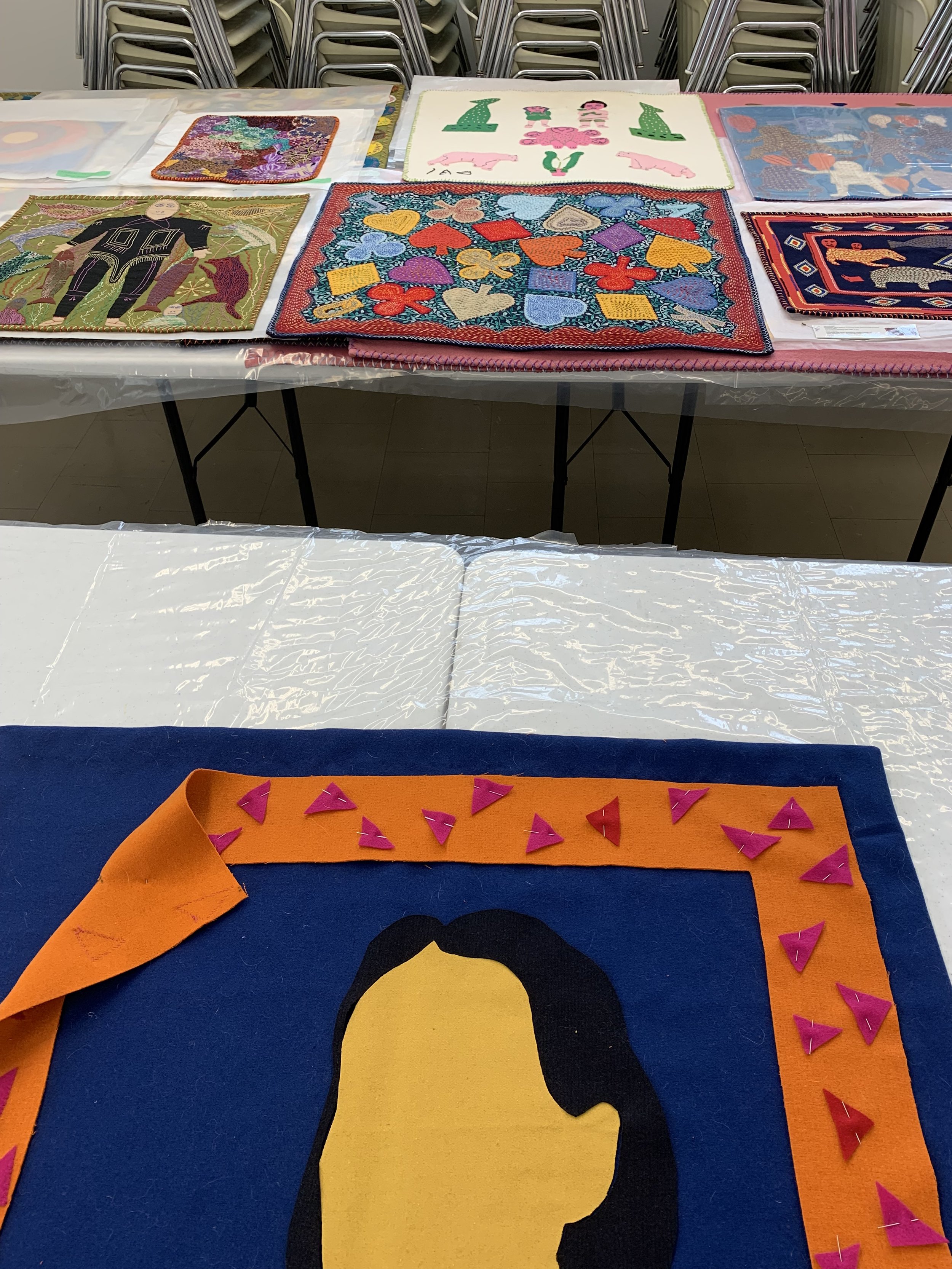

I started following the making of Tiriganiaq by chance on Instagram (@uyagaqi) this past winter and delighted in the details of the process shared by the artist. We spoke at the Art Gallery of Guelph in April as a large staff busily prepared the walls for the intergenerational conversation that now alights on them.

—Jesse Ruddock

Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona installing ᑲᔪHᐃᐅᑎHᐃᒪᔭᑦᑲ - Kajuhiutihimajatka at the Art Gallery of Guelph, 2022 | image: Jesse Ruddock

Jesse Ruddock

What was it like bringing out your family's work in the gallery? Did they bring it out for you? Or were you digging in the archive?

Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona

They brought out some pieces. They have a collection list and asked me which pieces I wanted brought out. They were really helpful and supportive. They said, anything you want. So we ended up bringing out a lot of the wall hangings, and the framed pieces are all in one room downstairs. There, you can just pull them out and look. We went through, Taqralik and I, with stickers, and we said, Okay, I really like this one, and this one would go well with my idea. I got to choose pieces that fit in with the narrative of my work. For some reason, there’s a lot of Baker art in the Guelph collection, and that worked out really well, because a lot of the people are my family members, or I know them, or my parents have stories about them.

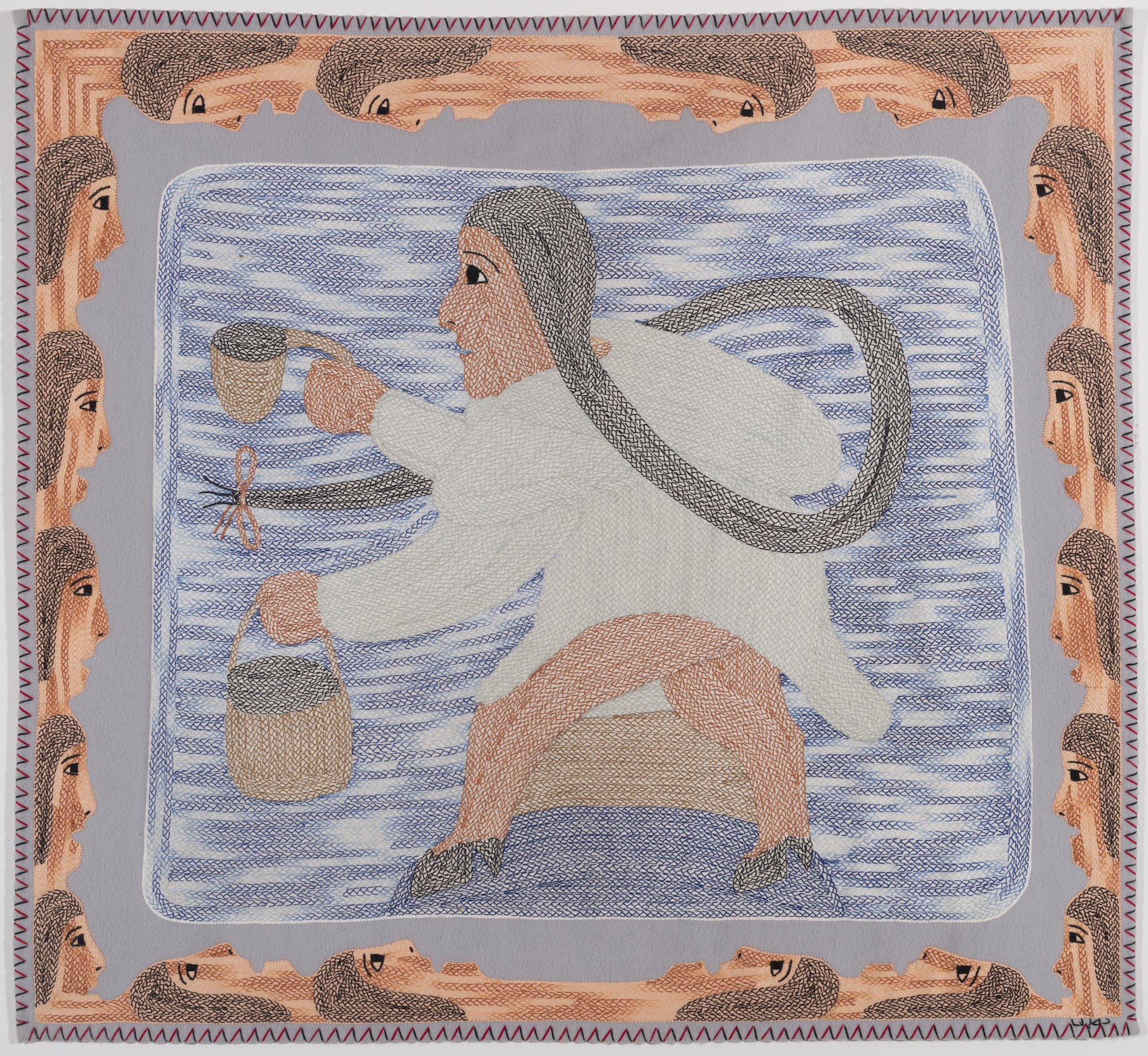

Victoria Mamnguqsualuk, Caribou Spirit Woman, circa 1997, wool duffel, felt, and cotton embroidery floss, 114 x 125cm | image: Art Gallery of Guelph

JR

I am a big fan of Taqralik Partridge’s art and poetry too. What has it been like to work with her as a curator?

GUK

It’s incredible. She knows so much, and she speaks Inuktitut. This is my first experience of having my art in a gallery, and working with an Inuk curator made the process that much better. We’re coming together to create something. I have my idea, and then she has input from all her experiences and knowledge. I think it lessens the burden on me to explain what everything is, how it’s significant, because she already knows. She’s within my own culture, right? It's been so good. She’s supportive and just wants to see other Inuit succeed, especially in the arts.

JR

It’s interesting that you describe it as a collaboration, because she's an artist, as well. So not just a curator? Seems like a powerful combination.

GUK

Definitely. When I was coming up with the sketch and trying to envision the type of wall hanging that I wanted, she had input, and I ran things by her. I asked, What do you think of this? In Taqralik’s mind, a lot of things were striking and certain elements were definitively Inuit, and she could bring her expertise into my vision of what I wanted to create.

JR

Your family’s art now accompanies yours on the walls, but it was lying dormant in the collection. You’ve opened it back up and are making it new again.

GUK

The legends pieces were all stories that my dad told me when we were out camping, and they are all really violent, and that’s where I got the idea to do the same stories but in a more equitable way, where it is not violence against women in every story.

JR

I read in your CBC interview that you were doing a feminist retelling of the Fox Wife story?

GUK

Yeah. In it, Kiviuq is the hero, kind of like a demigod, known across the Arctic. He can change forms and transform other things, and he has a lot of adventures. In one, he’s coming home and there’s a pot of caribou stew that somebody made for him, but there’s nobody home, and he keeps coming home and the same thing happens. So one day he hides to see who it is, and then he sees that it’s a fox who comes to make him stew and then she takes off. And she always takes her fur off to let it dry while she’s cooking. And so the day that Kiviuq hid to find out who it was, he steals her fur. And he says, I’ll give you back your fur if you agree to be my wife. So he has her as his wife and gives back the fur. And then they’re swapping wives with wolverines, and she doesn’t want to but Kiviuq does it anyway and tells the male wolverine to block all the doors so that she can’t escape. But he doesn’t, and she ends up escaping and runs away. And then there’s a bunch of tales of Kiviuq on adventures to go and find his Fox Wife.

JR

In your telling, she’s more empowered. I have wondered if the Fox Wife is a self portrait?

Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona, drawing for Tiriganiaq, 2022 | image: courtesy of the artist

GUK

It is, a little bit, for handiness. I use my own face as a reference photo because I can pose, and I can make it how I want things to look. But also, yeah, it is a little bit of a self portrait. The story that I wanted to show was that she left the relationship and he respected her wishes and left her alone. And she went and lived her life and was her own person. I think I’ve done that a few times, and definitely it’s been hard as a woman to not centre your life around relationships.

JR

It’s powerful to show this new piece in collaboration with your grandmother, great-grandmother, and many other artists.

GUK

It’s helped a little with the imposter syndrome.

JR

You’re not an impostor!

GUK

I was so surprised when the worst case of it came yesterday when I was surrounded by all of this physical evidence that I am an actual artist. I thought to myself, this is so weird.

JR

It seems that being an artist is being a maker, but it’s also understanding and being in conversation with other artists. And that is a strong element of this show. The conversation is literally in the work, in the stitching patterns, is that right? It seemed on Instragram that you were pulling stitching lessons from pieces in the collection.

Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona, Tiriganiaq, detail of work in progress, 2022 | image: Shelby Lisk

GUK

I have a few pieces that my grandma made, and I’ve seen many different wall hangings, but you don’t get super up-close when you’re looking at them. And so when I was deciding how to sew the appliqués on or how to do a certain decorative stitch, I would go and look at these examples, and see what they did. For Tiriganiaq’s paw, I did two stitches in the shape of a V, and then went back and saw what they were doing. It was one long stitch and then tacking it down in the middle to make the shape. I took everything out and redid it. For the strands of embroidery floss, I would look at how many strands they used, and anywhere from one to all six of the strands were used in different parts of the wall hanging.

JR

You practice a poetics of stitching.

GUK

In Inuit culture, I think a lot of people are perfectionists, and in a perfect world I would have learned these sewing skills from my grandma or from a relative or in a group. I’ve heard that when you’re learning how to make kamiks, the stitching has to be absolutely perfect. And if it’s not, you’re told to take it out and redo it. I was worried about Inuit women coming to the show and inspecting my stitching. I wanted it to be as accurate as I could make it to be respectful of the tradition. It had to be. I think the design elements were where I let myself go into my own thing.

JR

I love the orange colour. It’s in the border, the fox hand, the lipstick.

GUK

I love that really clear orange: opaque and gorgeous, bright orange. It probably comes from orange shirt day. And I have a really beautiful orange block printing ink that I use for my prints. It also was just practical. I went to a fabric store in Toronto on my way back from my first trip to Guelph and was looking at all of the Melton wool colours they had. In my mind, I was planning on doing a really stark contrast of black-and-white only.

JR

I would like to see that piece.

GUK

Hopefully I will get to do that at some point. Yeah, I couldn’t find white. I was drawn into blush and tan, all that kind of stuff, but it wasn’t really lnuit because there’s a lot of bright colours up there. And you can kind of see Who’s Who because, even if southerners have handmade parkas, they’ll go with a natural fur colour around the hood, whereas Inuit will have bright purple or bright yellow, all these bright, dyed colours.

JR

I wonder, did you find anyone that you connected to in the collection who wasn’t a relation, anyone new?

GUK

I did. I really like Luke Anguhadluq’s work, but he is a distant relative. There was also Fanny Algaalaga Avatituq. I posted one of her wall hangings on Instagram.

JR

The piece you shared is intricate.

GUK

Oh my goodness, it was like the whole thing was stitched!

JR

Are there other artists you think of as influences?

Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona, Tiriganiaq, detail of work in progress, 2022, at the Art Gallery of Guelph | image: Shelby Lisk

GUK

The little faces that I do are interpretations from Luke Anguhadluq’s artwork. I will look through auction sites when they have Inuit art auctions. I will like look at all of the things that they’re offering to sell, though I can’t afford to buy. I love looking at the older pieces, at what people were doing really early on.

JR

That’s interesting. That’s a strong resource, the online auction sites for seeing Inuit art. I’ve also noticed that it’s an amazing place to see pieces you haven’t seen before.

GUK

Have you seen the mugs that I make?

JR

I have.

GUK

I actually made those because there was a Luke Anguhadluq print that had colourful faces all over it. And it was pretty reasonably priced, maybe $300. I fell in love with it and actually bid on it. I think I missed out by $25, and I was like, well, it’s okay, I’ll save the money and I don’t need it anyways. But then a week went by and I thought, I actually really wanted that!

JR

A week passes, then you know something is haunting you?

GUK

Yeah, definitely. And I thought, Okay, well, what can I do? I don’t have it, but I could create something that reminds me of it. That’s where the little face mugs came from.

JR

What has it been like to be in residency here?

GUK

The first trip I took here was to look at the collection. I was looking at my great grandmother’s sketchbooks and getting an idea of what I wanted to do, talking with Taqralik, talking with Shauna. And on the second trip, I had all the materials and I had made the blue square, but I was stuck. We were in lock down, and there was the occupation in Ottawa. Coming here again, bringing everything, and being able to work in the space and get out of my own head and my apartment in Ottawa was good and was the push: no more thinking, time to get things done.

JR

Following your process on Instagram, it seemed wonderful from the outside, but it must have been a lot of pressure at times?

GUK

I haven’t been an artist for that long, and this was my first embroidery project, my first wall hanging and first big piece for an art gallery. I was the one putting all of the pressure on myself. But it was definitely like an exercise in managing myself and learning to make a work plan and do all of the technical pieces.

JR

I saw a picture of your plan. Because there are so many small elements that there has to be a plan or else it won’t come together?

Tiriganiaq, plans for work in progress, 2022 | image: Shelby Lisk

GUK

My grandma, I doubt that she did that. She probably knew exactly what she was doing all the time, because she had experience. But how my brain works, I’ll get ahead of myself. Something that struck me when I was looking at my great grandmother’s sketchbook was that everything was composed perfectly and fit the paper. There were no sketch marks. It’s just, this is the image, and this is it. I was talking to my sister about that, how everything was just so perfect. And she said, back in the day, if you put a ton of work into skinning a caribou and drying it and fleshing it and cutting out the pattern of a parka, you were being careful and meticulous in every single step. So every movement was assured, because it had to be.

JR

The same method crosses materials.

GUK

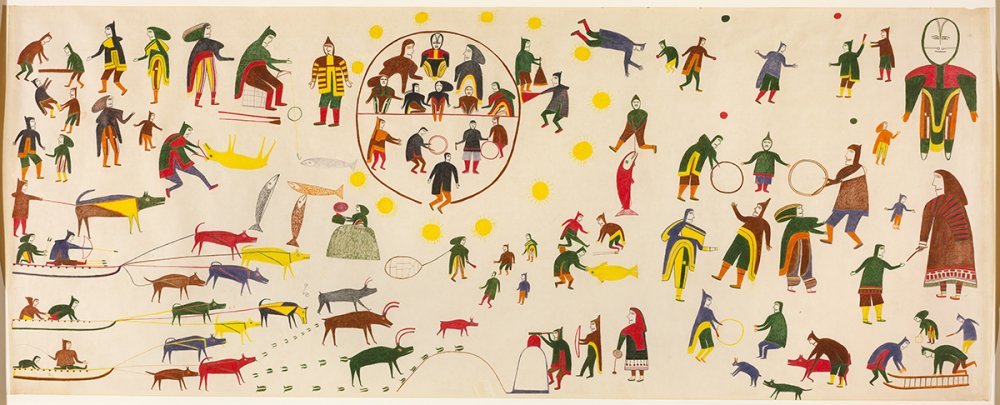

When I was in Baker last summer, my dad was telling me that somebody in the community gave my great grandmother a big sheet of paper as a gift. And she made a huge drawing. It’s at the National Art Gallery. It’s this really long sheet of paper, and she did the spring celebration.

JR

Wow, I’ve seen this piece and didn’t wonder at its dimensions, even though they are striking.

GUK

He gave her the paper, and it was assuming that she would cut it down and make a lot of different smaller works. But then he came back and she had drawn this massive masterpiece.

Jessie Oonark, When the Days are Long and the Sun Shines Into the Night, 1966–69, felt pen and graphite on wove paper, 127 x 318 cm | image: National Gallery of Canada

JR

Kajuhiutihimajatka is translated as “Things I’m Carrying On” and “What I’m Carrying On.” I saw two different translations and was interested in the difference.

GUK

In the beginning, it was “things.” I think that translates better, but how do we feel about the word things?

JR

Things signal objects or just stuff? Maybe using what in the title is a more open gesture? I like both titles.

GUK

These decisions felt really big at the time. It was a huge open question. What’s one word for the idea I’m trying to achieve? My second cousin helped me name the exhibit Kajuhiutihimajatka.

JR

If I were to ask, what are you carrying on, is that too big of a question?

GUK

It’s being an artist, and I think that being an artist when I grew up wasn’t really an option. Starting with my dad’s generation, there was a push to get people into jobs and careers. And I felt that too, and I went to university and was an urban planner and did a range of professional things that I really didn’t like, and it never felt right.

JR

Because you're an artist.

GUK

Yeah, and it has to do with the actual wall hangings, and with sewing, but also with keeping the legends being talked about and part of current culture, because I think it might be older people who know the legends, and maybe they’re not carried along, or they don’t fit with contemporary sensibilities.

JR

Your Fox Wife piece brings it all together.

GUK

It’s interesting to think about the initial viewer experience, and then trying to get the meaning that you want behind it.

Following her family lineage of Utkuhikhalingmiut Inuit artists and printmakers, Ottawa-based multidisciplinary artist Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona is known for her intimate artwork with striking graphics exploring imagery inspired by Inuit community, stories, and culture.

Jesse Ruddock is a Canadian-American writer and photographer. She is author of the novel Shot-Blue (Coach House, 2017). With Effy Morris, she co-founded O BOD in 2021. She lives on the traditional territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, in Guelph, Canada.

Grateful acknowledgment to photographers Shelby Lisk and Nathan Saliwonchyk.